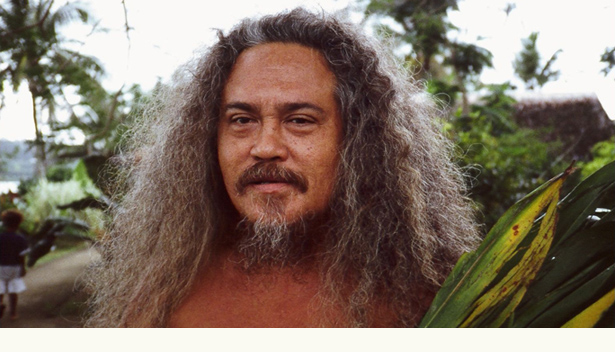

Portrait of Ariipaea 'Paea' Salmon. Photo by Chris Kilham

Tribute to Ariipaea 'Paea' Salmon

(Paea passed away on March 21, 2011)

There is something terribly exhilarating to stepping off of perfectly good ground into a burning furnace of uneven volcanic stones, made red-hot by tons of blazing timber underneath. As I stood at the edge of the huge fire pit, all my accumulated knowledge of unbendable physical principles dissolved away. My nerves vibrated like struck piano wire. My abdominal muscles quivered. The radiant heat from the fire baked my legs and chest and face. I took two deep, broiling breaths and stepped into the fire. All thoughts, notions, concepts and ideas ceased in an instant. There was only fire, stone, walking.

My friend Ariipaea Salmon, who I know as Paea, had walked first. As the Tahua, the keeper of the fire, he directed all the preparations leading up to the walk itself, and appealed to the gods and spirits to tame the fire so the rest of us could safely cross the stones. After Paea, Kami walked. A kava grower from the island of Pentecost, Kami was part of the native crew that had prepared the fire, an undertaking of mammoth labor that took a couple of weeks. I had hiked remote jungle trails behind Kami on Pentecost island at other times, and now I was following him across a fire pit on Vanuatu’s capitol island of Efate’. I had never firewalked before; neither had he. You just never know where you’re going to wind up with the people you meet.

Behind me, Jonas and two dozen other men from the traditional Pentecost island villages of Bunlap and Baie Martellie readied themselves to walk. So did Paea’s son Heiariki, and Simon Agius, a young man who worked side by side in the preparations with Paea. But behind all of us, like a sorcerer whose incantations and spells are felt but not seen, lay kava, a Pacific island plant whose psychoactive potion dissolves the cares of a stressed or weary mind, and links the drinker with the spirits of ancient gods.

The history between plants and humans points to a grand closeness. By various means plants touch the deepest and most vulnerable spots of the human imagination. They cause us to perform great feats and labors, carrying them on our backs all around the world. Plants inspire some, and drive others to madness. The assumption that the action of plants upon humans is merely physical or chemical strips essential mystic sinew from the corpus of life. Like reading only every other word of a fabulous book, you may catch the drift of the tale, but the full story and its meaning remain unknown. We eat plants, drink their juices, wear their fibers, scent ourselves with their fragrances, build homes and structures with their materials, adorn our property and bodies with them, employ them to alter mind and mood, are attracted by their beauty or oddness, and are deeply moved by them. Influential agents that they are, plants drew me into the sacred native ceremonies of the South Pacific, and into a burning furnace.

I was never interested in new age firewalking empowerment workshops. Not that I ever derided the act of firewalking, or ever questioned the danger of doing so. Fire is dangerous and hot, whether in a Marin County back yard or on a remote Pacific island. Call it purist conceit, but I determined that if I ever firewalked, it would be in a traditional native setting. That opportunity arose in the spring of 2000 when my close friend Ariipaea Salmon called me from the remote South Pacific archipelago of Vanuatu, where he lives. “Hello, Chris,” Paea’s resonant voice called through the lines. “I have something important to tell you. I have decided to put on a firewalk for the full moon of August. Will you come?” He knew the answer before calling. Of course I would come. I had to.

In November of 1999, a midnight earthquake at sea generated a gigantic tidal wave, or tsunami, which slammed into Vanuatu’s Pentecost island. Several villages were destroyed. Thirty foot waves dragged bamboo huts, coconut trees, and all the personal effects of the coastal village people, out to sea. They were left with nothing. Remarkably, only seven people were killed by the wave, which could have claimed the lives of dozens or even hundrds more natives. Among the villages hardest hit was Baie Martellie, a tropical paradise of pretty bamboo houses and swaying coconut palms. The picturesque and remote village at the very southern tip of Pentecost sat like a jewel on a pristine, sandy crescent beach. Baie Martellie was the idyllic native tropical village. Then the tidal wave hit, and Baie Martellie was swept out to sea.

Baie Martellie was where, in 1995, Paea and I first came to know each other. Kava led me there. I was investigating the tranquility-promoting kava, Piper methysticum , for possible extraction and marketing in the US. Through a series of contacts I wound up meeting Paea and staying in the picturesque village of Baie Martellie, and our close friendship began. I became friendly with many of the kava growers there, and spent happy times walking with them in the jungle, preparing and drinking kava, and participating in their village life. They accepted me wholeheartedly, and I promised to help them over time as I could. When Paea informed me that the firewalk would help to raise relief funds for our friends in Baie Martellie, I had no choice but to go and walk. I booked passage, and wondered what it would be like to step into a burning fire pit. “The fire will be the biggest one ever in Vanuatu,” Paea assured me. “I will build a pit at least fifteen metres long. The fire will be very powerful, very cleansing.”

My first time walking across the twelve foot width of the fire, I burned a spot on the arch of my right foot. I was not willing to let that be my only firewalking experience. Three subsequent times across the same stones, I walked without mishap. When I lined up with Paea and the Pentecost island villagers, we walked the full length of the fifty foot pit safely. The glowing stones were hot enough to fry a steak in seconds. Flames licked up between the rocks. It was like walking the gnarled spinal ridge of a gigantic dragon. The uneven footing would have made walking precarious without a fire. In the roasting heat of the pit, where forty tons of timber burned beneath fifty tons of volcanic stones, we should have been immolated. Yet we passed through the burning furnace safely.

I have heard a few humorous explanations for firewalking. One is that you get into a mental state in which you are impervious to burning. If that notion were valid at all, then individuals who believe faithfully that they can fly, would not injure or kill themselves jumping out of high windows. Another quaint theory is that the incipient sweating of the soles of the feet prevents burning by creating a thin film of moisture on the skin. Lastly, I have been told that volcanic stones never really get that hot, and that a fine layer of ash settles upon the stones, and this prevents burning. All these wonderfully absurd theories arise, of course, from those who have not walked.

The world is filled with those who engage in direct experience, and those who speculate, theorize, second guess, postulate, and concoct a myriad of abstract notions. Those who engage in direct experience share an advantage that the theoreticians can never get close to. They know what it is like to throw oneself wholeheartedly into an activity, the others do not.

I believe that the simple truth of firewalking so stretches the boundaries of the mind, most people would rather believe in the silly theories above. I accept that the “secret” to firewalking is exactly as natives describe it. You build a huge fire, you propitiate the gods and spirits, they tame the fire for your passage, and you walk safely. This spiritual protection saves the firewalker from horrible injury or death. This is not just the secret to firewalking; it is a life secret. Magic works as long as there are those who accept it and commit bold acts by it. And the magic dies out when there are no longer any believers.

Dear Friends,

It is with tremendous sadness that I want to let you know that Ariipaea 'Paea' Salmon has died. As you know, he and I were very good friends, and we had many excellent times together, nearly losing our lives in each other's company, firewalking, drinking kava, and barging around the South Pacific and the US with loads of energy and bluster and a sense of fun and mission. I do not know yet the details of his death, but he had serious cardiovascular problems, and had suffered a stroke a few years ago.

All of you who also knew Paea and had your own experiences with him know he was legitimately a prince. As far as I am concerned he was born in the wrong era, as he would have made a spectacular tribal warlord or royal in more primitive times. Of the experiences I have enjoyed with friends, some of my times with Paea stand out as among the most memorable.

I will miss Paea greatly. Though he was immensely irrascible, he was also one of the most humorous, visionary and affectionate friends I have ever had. My memory of our last firewalk (which I knew right then was our absolute last walk together) will stand out in my mind and heart as one of the most powerful and mysterious of all times I have lived.

Paea was one of a kind. He is someone who lived larger than life. Many of us will miss his roaring laugh, his amazing smile, his heroically overblown ideas. At some point, in your own way, please raise a glass (or whatever) to the memory of a fallen friend.

Much Love,

Chris

March 21, 2011